Choosing an AAC Device for Your Angel

Written by |

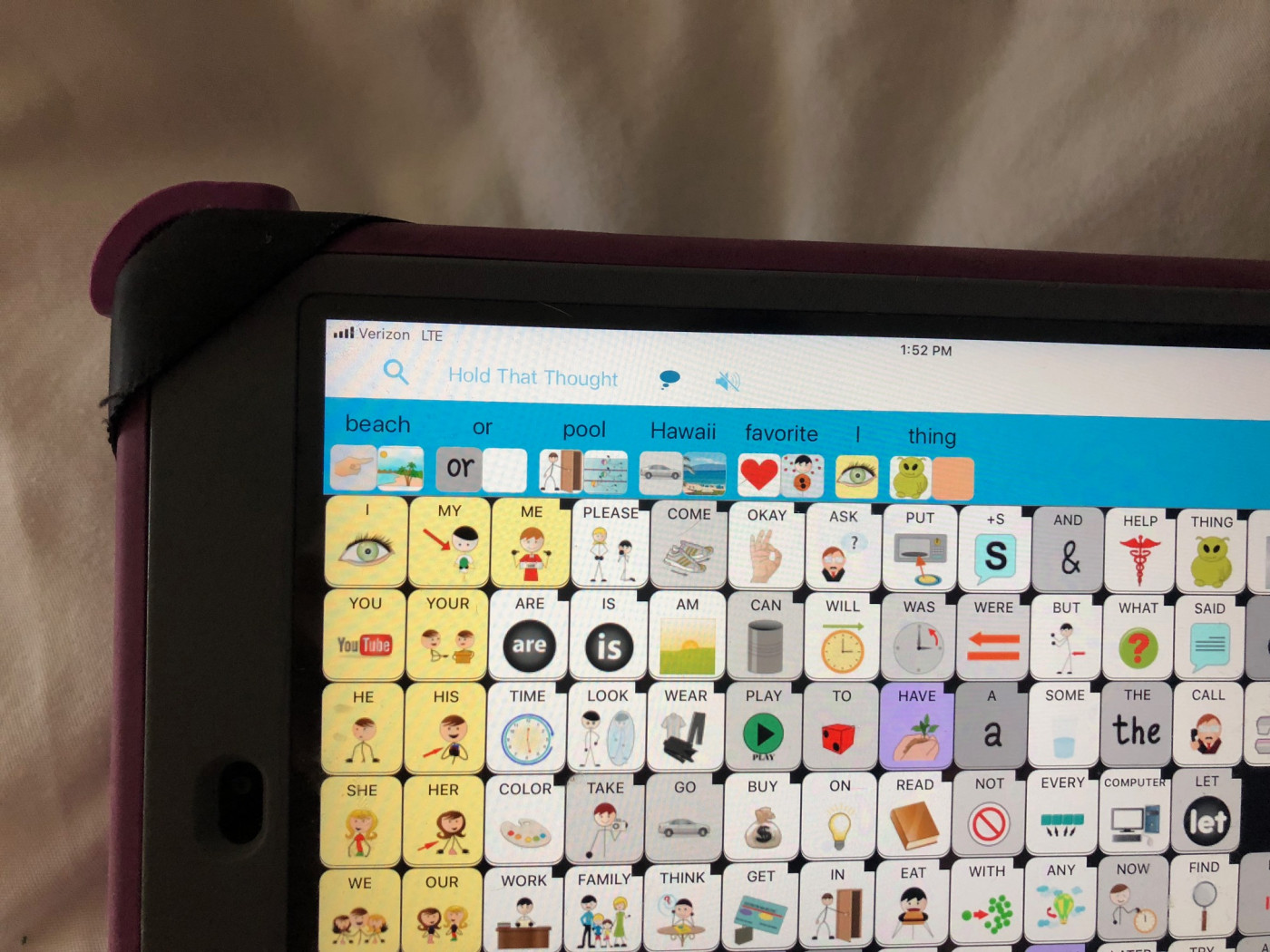

"beach or pool Hawaii favorite I thing" she used a word approximation for think. Courtesy Mary Kay

If anyone ever asks me what is the best augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) device for their child, my response is, “the one they will use.” I know that doesn’t answer their question, but it is what we’ve learned to be true.

Jess had two significant AAC evaluations. The first was when she was 8 years old. The evaluator determined she should have a device that was robust and gave her a wide range of words. We were recommended a popular device.

The first six months were exciting. Jessie was intrigued by the device and could use it to make simple requests. However, when it came time to add more language, the template changed to one where the grid and the words were smaller.

However, the size of the words wasn’t the issue. The problem was the change in the motor plan. Motor planning is at the heart of how these devices work. When the user learns where a word is, they don’t have to think about the location; their finger will hover in the general area and their hand will go to where the word is. When this happens, you will notice they can tap their words faster.

To help someone to understand how ingrained our motor planning is, I relate the example of when we changed the hinge of a door in our house and moved the doorknob. For the first few weeks, I kept reaching for the knob expecting it to be in its usual place. Months later, I would still reach for the wrong side of the door. It takes time to relearn a motor plan: Think about how frustrating it would be if someone changed a few keys on your keyboard.

Over time, Jess stopped wanting to use the device. She realized she could have her needs met faster by using nonverbal communication than with the Talker. What I didn’t understand at the time was that to find the robust language, she had to tap through layers. These extra steps slowed her down and it was difficult for her to remember beyond the second layer, especially as her vocabulary grew.

The other significant AAC evaluation Jessie had was when she was 20. They said she did not have the fine motor skills, attention span, or cognitive ability to use any of the iPad apps that were available. Instead, a program that had a very boring, basic language was suggested to us.

No one understood why the other programs had failed, and we were left with few choices.

It was a Hail Mary move to go against the expert’s advice. However, networking with another parent led me to the app “Speak for Yourself.” According to the “experts,” it shouldn’t have worked — but it did. It worked because it relied on a consistent motor plan; Jess learned one word at a time (just as a typical child learns a language), and she had more words at her fingertips using the Babble feature.

It’s important to note that we had to improve Jessie’s skills so she could have success with an AAC device. We worked on specific fine-motor activities to help her isolate her finger and we did this through play. For example, we purchased a gumball machine. Jess had to pick up a quarter, put it in the slot, turn the crank and then open the tiny door to dispense M&M candies. When she began using Speak for Yourself, she started with a full-sized iPad with a key guard which encouraged her to isolate her finger. It also was necessary to have the iPad be ergonomically correct. It needed to be on a stand and not flat on a table. Because Jess wasn’t able to close her hand (at the time), her fingers would dangle and she’d touch words by accident.

Don’t blame your child if he or she has lost interest in their AAC device. Maybe they are bored with it. Perhaps they can’t find the words they want to say because they have to tap through layers. We didn’t understand why the other AACs didn’t work for Jessie until we changed programs.

The bottom line is if they lose interest in their device then maybe it isn’t meeting their needs.

Whatever AAC system you choose it needs to be easy for you to support. I suggest that you try using the program in a real-life situation — only then will you understand what you are expecting your child to do. The most important thing is that your child has a voice.

***

Note: Angelman Syndrome News is strictly a news and information website about the disease. It does not provide medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. This content is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition. Never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read on this website. The opinions expressed in this column are not those of Angelman Syndrome News, or its parent company, Bionews Services, and are intended to spark discussion about issues pertaining to Angelman syndrome.

Leave a comment

Fill in the required fields to post. Your email address will not be published.