Everyone Missed the Signs

Written by |

Every Angelman syndrome person has a different story. This is the beginning of ours.

Once Jess was diagnosed and labeled with cerebral palsy (rather, misdiagnosed), we were directed to an early intervention program. Through play, she was immersed in language and cognitive skill development. I thought this was just the support that she needed to catch up!

My dreams were squashed. At the end of the school year, Jess was asked not to return. The school said, “We only want to work with children that we can help.” The school directed us to a cerebral palsy (CP) center.

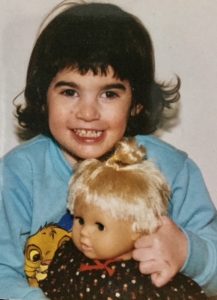

This was difficult to hear, but now, many, many years later, I realize they were telling me Jess was beyond their ability. I didn’t get it. Jess was such a sweet and happy little girl. How could she be such a challenge? It was a sign.

While at the first school, Jess had fallen a few times. She’d be walking one moment and on the ground the next. The school suggested seeing a neurologist. Jess fell a lot. She had bruises up and down her shins but, from what I saw at home, this was due to her poor balance and ataxic gait.

After watching Jessie walk, the neurologist didn’t think there was any cause for concern. However, I shared how Jess would stiffen her body for a few seconds when she was lying down and asked if that was a seizure. She poo-pooed me out of the office and dismissed my worries. This was a sign.

Another issue was that Jess’ eyes didn’t work in unison. Her right eye was beginning to turn inward. The first treatment was to put a patch over the stronger eye to force the “lazy” eye to work. Jess wore this without objection for six months. The first day she attended the CP center, a classmate pointed to her and asked, “Why are you wearing that?!” At 4 years old, Jess felt self-conscious and immediately pulled the patch off, refusing to wear it. Our only alternative was to have strabismus surgery. This surgery initially appeared to be successful, but there was more going on “than meets the eye.” Because of her vision issues, Jess had problems with depth perception. Like a blind person using a cane, Jess would tap a foot out ahead of her when the floor transitions from one material to another. She needed to know if the floor was flat, or to take a step up or down.

In housing terms, what we lacked was a general contractor for a child with complex medical needs. Someone who could cull the information we had collected from school, therapists, and doctors to make sense out of it. Jess had been dissected into parts and not treated as a whole. If we had such a person in place, it would have been obvious that her hand-eye coordination, as well as depth perception, were connected.

Of course, this didn’t answer why Jess wasn’t talking. This mystery wouldn’t be solved for years. However, if they had been more on point, Jess should have received more effective therapies to improve the skills she needed for communication — such as isolating a finger and recalibrating her eyes. If she is unable to talk, she needs some form of augmentative and alternative communication (AAC), but we wouldn’t learn about this for years.

I’m ashamed to say how many years it took me to figure this out on my own. For longer than I care to admit, I left the big decisions to the professionals. As they reminded me, they were trained and knew more than this mother. They intimidated me because they were the educated ones. However, when it came to Jess, I am the expert. As big as these challenges were, these weren’t as scary as the medical challenges she was going to face.

There’s no doubt in my mind that in Jess’ secret school transcripts (a file that parents aren’t allowed to see) there is a notation that refers to me as an “over-involved parent.” (One teacher recently shared that someone warned her about this over-involved Mom.) I insisted on knowing what Jess did at school so I could work with her at home. I felt (and still do) that school and home need to be on the same page, but it isn’t done that way. If I had access to information, I would have challenged the status quo. Unfortunately, this was years before Google and well before Facebook made it possible for parents and professionals to share information. All the signs were there. We just didn’t have anyone who knew how to read them.

To read more about our journey, visit my blog (we wouldn’t even have a story if Jess hadn’t found her AAC voice) and check Angelman Syndrome News on Fridays for my upcoming columns.

***

Note: Angelman Syndrome News is strictly a news and information website about the disease. It does not provide medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. This content is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition. Never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read on this website. The opinions expressed in this column are not those of Angelman Syndrome News, or its parent company, Bionews Services, and are intended to spark discussion about issues pertaining to Angelman syndrome.

Leave a comment

Fill in the required fields to post. Your email address will not be published.