US Network of Specialized Angelman Clinics to Double Thanks to New Partnership

Written by |

A network of 22 clinics worldwide will now specialize in Angelman and Dup15q syndromes.

As part of her medical training, North Carolina pediatrician Elizabeth Jalazo had studied a little about Angelman syndrome.

“I knew enough about it to answer a board question, but I didn’t know the complexity of the disorder,” she said. “I’m sure most general pediatricians would share the same sentiment.”

Then Jalazo gave birth to a daughter with Angelman — and she quickly became an expert on the disease. Evelyn, now 5, is the second of three siblings; there’s also Anna, 7, and Charlie, 2.

“I didn’t know immediately that she had Angelman, but I knew there was something different about Evelyn within five days of her being born,” Jalazo said. “As most families, we endured a yearlong odyssey of diagnosis. And that was only because I was a clinician at a hospital that had a developmental center where I could push for her to be evaluated.”

At the time, Jalazo was a chief resident at Baltimore’s Kennedy Krieger Institute — a division of Johns Hopkins University — “so I could pick up the phone and ask a professional favor. I basically skipped 9-12 months of wait time.”

Jalazo now is a full-time clinician at the University of North Carolina (UNC) School of Medicine in Chapel Hill, where she sees kids with Angelman, Hunter syndrome, and other genetic disorders.

For the past six months, she’s also been director of clinical integration at the Chicago-based Angelman Syndrome Foundation (ASF), a nonprofit group dedicated to finding a cure for the severe neurological disorder that affects Evelyn and about 25,000 other Americans.

ASF, Dup15q Alliance join forces

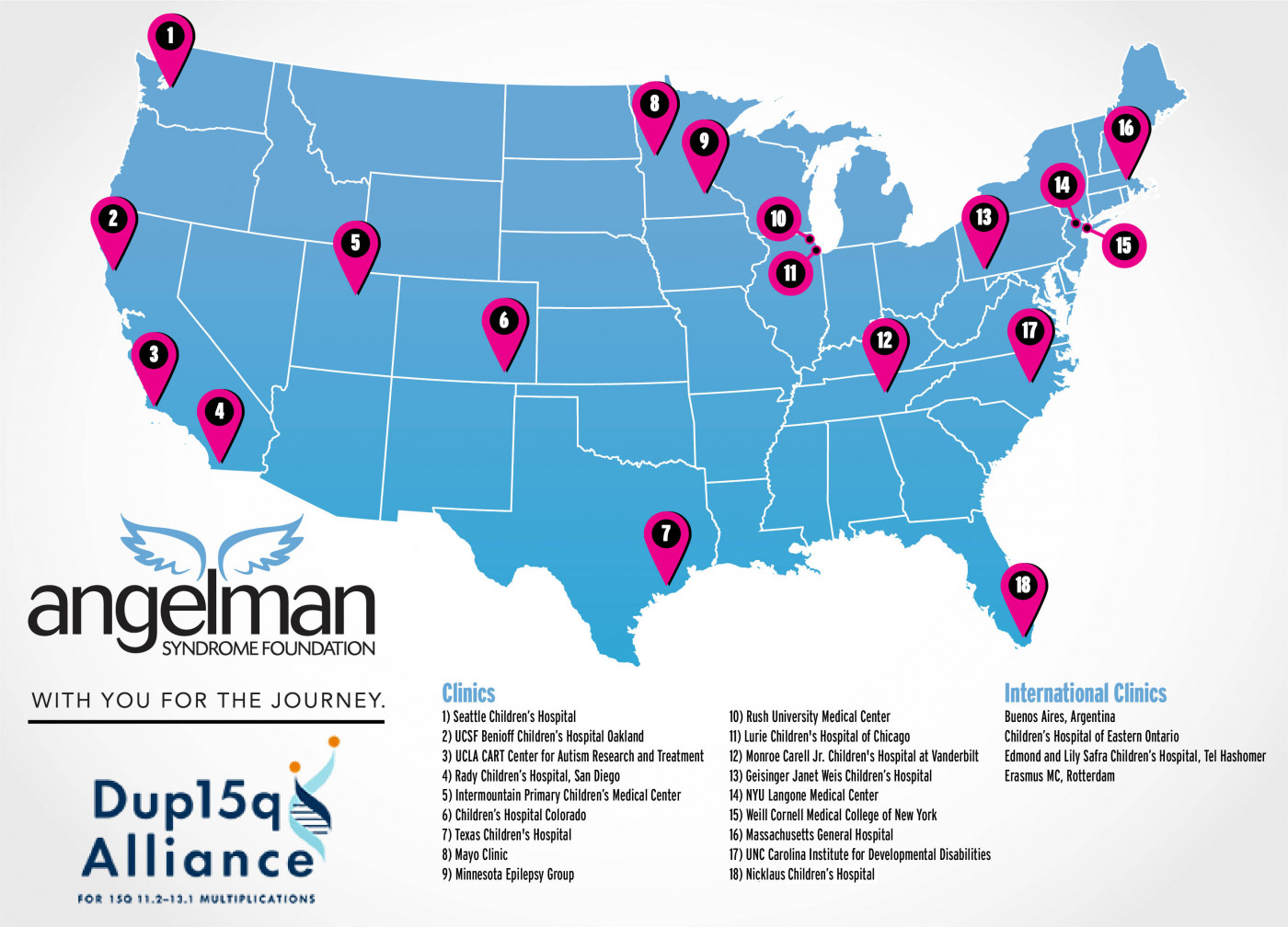

The U.S. network of specialized clinics Jalazo oversees is now set to more than double in size — from eight to 18 — thanks to a new partnership between the ASF and the Dup15q Alliance. The network also includes four non-U.S. clinics, in Argentina, Canada, Israel, and the Netherlands.

The 15q Clinical Research Network, as the joint effort is known, will serve patients with Angelman and dup15q syndromes — both rare conditions that stem from mutations in the same region of chromosome 15.

In Angelman, the mutation is most commonly a microdeletion on chromosome 15 encompassing the UBE3A gene. This prevents the production of the UBE3A enzyme in certain brain regions.

“Partnering with the Dup15q Alliance will allow us to increase our reach to the AS community and provide the best care for our families,” Amanda Moore, the foundation’s CEO, said in a press release. “Comprehensive and specific care is critical for AS families throughout the stages of their journey — by partnering with Dup15q Alliance, we are able to reach thousands more families with care and support by bringing AS clinics to their location.”

The ASF operates on an annual budget of $2 million and uses half of that to fund research. It currently serves 3,500 patients in the database and has around 22,000 followers on social media.

The network Jalazo supervises began in 2011, when three specialized Angelman facilities — at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, UNC’s Carolina Institute for Developmental Disabilities in Chapel Hill, and the NYU Langone Medical Center in New York City — all became ASF-supported clinics. Six more were added over the last eight years.

“Patients travel to where they can receive this evidence-based care,” said Jalazo, who spoke to Angelman Syndrome News at the 2019 NORD Rare Diseases & Orphan Products Breakthrough Summit, organized by the National Organization for Rare Disorders.

“When it’s challenging to travel with a child that has special needs — especially one with a rare disorder that no one’s ever heard of — it becomes incredibly beneficial to see all the specialists you need to see in one or two days,” she said.

10 clinics to join 15q clinical network

Most of these clinics operate one day a month, though some sites such as Mass General see patients weekly. The current U.S. network treats around 700 Angelman patients throughout the United States; including the four foreign clinics, the ASF network serves close to 1,000 patients.

In December 2018, Israel’s Sheba Medical Center at Tel HaShomer joined the network. That specialized AS clinic, housed at Sheba’s Edmond and Lily Safra Children’s Hospital just outside Tel Aviv, was established seven years ago by pediatric neurologist Gali Heimer. Since then, it’s evolved into the fourth-largest specialized Angelman syndrome clinic in the world, treating 85 of Israel’s known 100 or so Angelman patients.

Thanks to the new agreement between ASF and Dup15q Alliance — both based in the Chicago area — 10 Angelman clinics will join the ASF network, including Seattle Children’s Hospital, Miami’s Nicklaus Children’s Hospital, and the Intermountain Primary Children’s Medical Center in Salt Lake City, Utah.

This isn’t the first time ASF and Dup15q Alliance have worked together. Because the two syndromes are similar, the groups have co-hosted a research symposium every two years. Many researchers who study Angelman also study dup15q.

“Our goal is to bring together all the providers caring for Angelman individuals across the globe,” Jalazo said. “We encourage our sites to be multidisciplinary, so that patients can receive comprehensive care, but we do recognize that some clinicians around the world are not seeing patients in a multidisciplinary setting.”

As clinical director at the ASF, Jalazo oversees a monthly virtual meeting via Zoom where representatives of all the clinics talk about pressing issues.

“One of the biggest challenges is harnessing the power of patient data,” she said. “Every time a patient shows up at a clinic, an incredible amount of data is collected that’s valuable to patient care, to understanding the natural history of the disease, and to drug development. So we want to harness that and ensure we’re utilizing and formatting it in a way that’s accessible.”

An ‘exciting time’ for AS research

Jalazo said that when it comes to her own daughter, an early diagnosis definitely helped. Evelyn has been on a modified ketogenic (low-carb, high-fat) diet from a very early age.

“She eats whatever’s put in front of her,” said the pediatrician, adding that Evelyn generally eats eggs and avocados every morning. “She’ll go find the blender and if it’s 3 p.m. and I haven’t made a smoothie, she’ll bang the cup on the counter.”

Indeed, though the little girl can’t speak, she does communicate.

“If she needs something, she’ll go get it and bring it to me. She’ll force eye contact. Before she could even walk, she’d scoot over to you and direct your gaze over to whatever she wanted you to see,” Jalazo said. “I think she understands most of what I tell her. There are certain tones she uses. Her term of endearment is a ‘g’ sound which means ‘I love you.’”

Evelyn’s sister, Anna, is a “natural caretaker” and knows intuitively what Evelyn needs, while Evelyn and Charlie have a “very typical sibling relationship” — they fight all the time, Jalazo said.

“She’s completely nonverbal and you’d assume she can’t read the cues of social situations, but she and Charlie communicate 100% effectively,” she said.

As for a cure for AS, Jalazo said gene therapy is “extremely promising” but that short-term, the focus is on antisense oligonucleotides, or ASOs. These are small pieces of DNA or RNA that can bind to specific molecules of RNA and reduce, restore, or modify protein expression.

“It’s an incredibly exciting time for the Angelman community, in terms of promising therapeutics coming down the pipeline, one of which is gene therapy,” she said. “In the immediate future, we’ll have the opportunity to see the impact of non-gene therapy approaches like ASOs. This will give us a little sneak peek into what gene therapy can do.”