Israeli Angelman Syndrome Clinic Earns Global Respect

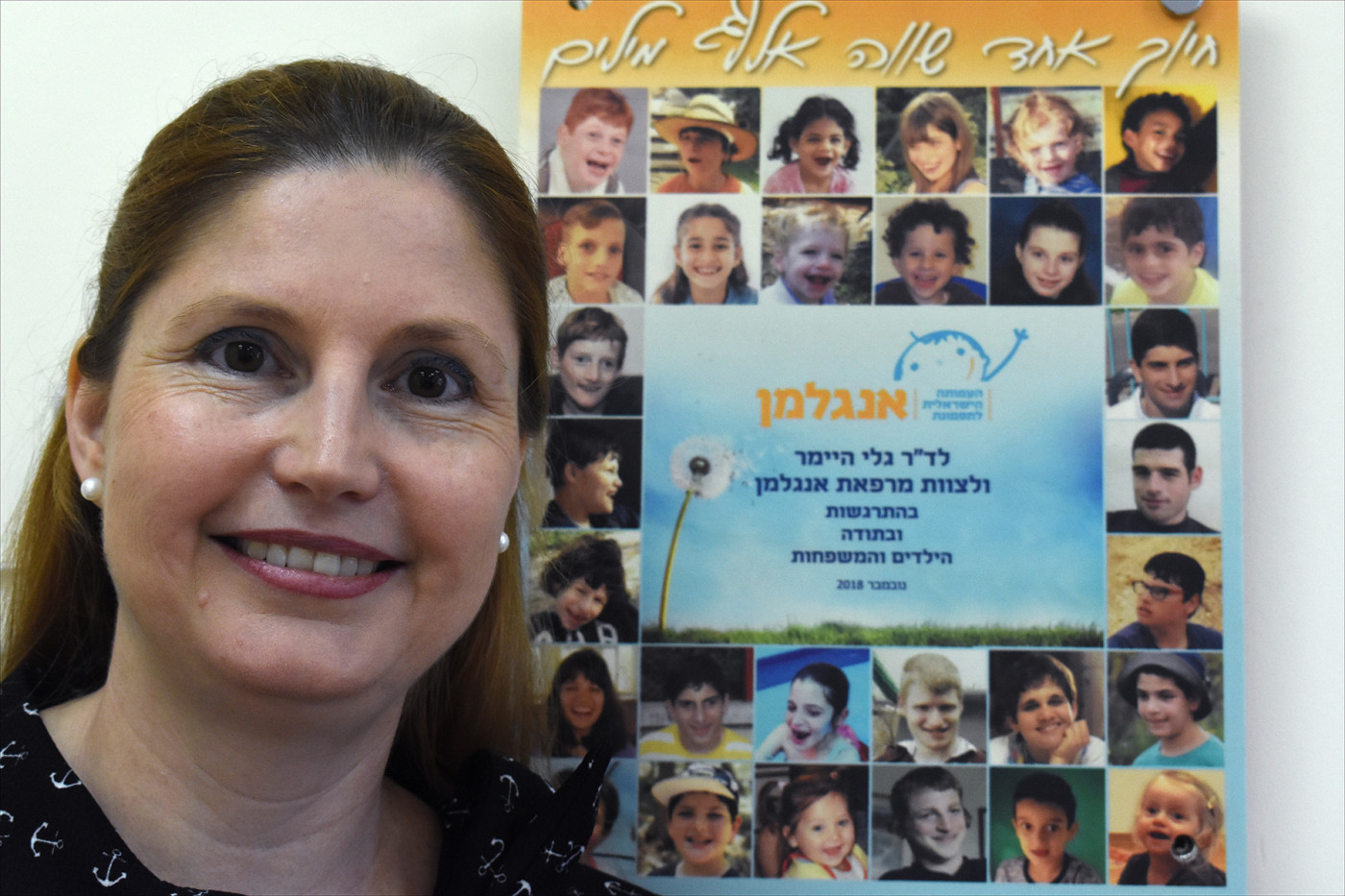

Gali Heimer, MD, is director of Israel's Angelman Syndrome Clinic, which is part of the Sheba Medical Center.

Israel’s Sheba Medical Center at Tel HaShomer already ranks as one of the world’s 10 best hospitals, according to Newsweek magazine.

Now, the institution has a new accolade: it’s the first anywhere outside North America to join the international network of specialized clinics accredited by the Chicago-based Angelman Syndrome Foundation (ASF).

The clinic, housed at Sheba’s Edmond and Lily Safra Children’s Hospital just outside Tel Aviv, was established seven years ago by pediatric neurologist Gali Heimer. Since then, it’s evolved into the fourth-largest specialized Angelman syndrome clinic in the world; only two U.S. clinics and one in the Netherlands treat more patients.

Heimer and her colleagues currently treat 85 of the country’s 100 known Angelman patients, in partnership with the nonprofit Israel Angelman Syndrome Foundation. Some come from as far south as the Red Sea port of Eilat — and others from as far north as the Golan Heights, along Israel’s border with Syria.

“It’s a three-hour drive from each place, but this is the advantage of being a small country,” said Heimer, who had sporadically been treating 30 Angelman patients long before the center’s establishment. “Families can come and see all the experts they need on the same day.”

Based on Israel’s population of 9 million, the Middle East nation should statistically be home to at least 400 Angelman patients — with one-third of them over the age of 40.

“The reason we don’t have 400 is that when many of them were born, there was no good testing for Angelman,” Heimer said. “A lot of relatively old undiagnosed patients are probably being taken care of in group homes, where they’re considered ‘intellectually disabled.’”

One-stop shop for Angelman

The physician spoke to Angelman Syndrome News in early September from her office on the second floor of the brightly decorated children’s hospital, whose façade is decorated with giant purple alligators.

The Angelman clinic at Sheba, which joined the ASF’s network in December 2018, generally operates once a month (though sometimes twice), and always on a Wednesday. It involves Heimer and five other professionals: an orthopedist, a dietitian, a psychiatrist, an endocrinologist, and an adolescent specialist.

“This holistic approach saves families the need to come back many times, which is very difficult, especially for people who don’t live nearby,” said Heimer, who makes it a point to sit for an hour with each patient. “Another advantage is that over time, our physicians see a lot of Angelman patients and become experts on the subtle nuances of treating the disease.”

A third benefit of having an expert Angelman clinic, said Heimer, is that the critical mass of patients it creates enables Sheba to attract clinical trials to Israel — and ultimately, new therapies for those who need them.

Angelman syndrome, a complex neurological genetic disorder, occurs in about 1 in 15,000 births. Most people with the incurable illness can’t speak; they also have numerous other physical and mental disabilities. Unlike Gaucher disease, Tay-Sachs disease, cystic fibrosis, or other illnesses known to strike Ashkenazi Jews — those of European descent — especially hard, Angelman is an equal-opportunity syndrome without any racial, ethnic, geographic, or gender component.

Chromosomal microarray (CMA) prenatal diagnosis for Angelman syndrome only became available in Israel five years ago; this allows doctors to identify the 70% of cases that are not usually hereditary. However, about 10% to 15% of Angelman cases which can be potentially hereditary, or are caused by other genetic defects yet to be identified, cannot be detected by CMA.

“I have a lot of families tell me they’re glad testing wasn’t available when they were pregnant, because they really love the child,” said Heimer, adding that prenatal diagnosis and abortion remain highly controversial issues in Israel. “This is a very personal decision for every family.”

‘Talk to your kids all the time’

Heimer said that ever since childhood, she’s been interested in the human brain. But the doctor — who studied at Jerusalem’s Hadassah Medical Center and has a PhD in the neurobiology of Parkinson’s disease — discovered that she much preferred working with children than adults.

“I flourish when I treat kids. So I did a detour, studied pediatrics and then pediatric neurology,” said Heimer, who’s been at Sheba for the past 10 years. “When I finished my pediatric residency, I had to decide between being a geneticist or a pediatric neurologist.”

Heimer and her specialized Angelman team help patients not only with serious issues such as seizures and digestive problems, but also with “trivial difficulties” such as sleep disorders, behavioral disorders, constipation, and drooling, which can overwhelm parents and caregivers.

“It can really be overwhelming,” she said. “Sometimes you have to change your child’s shirt five times a day. So if you manage to treat the drooling, it helps their quality of life.”

Another big issue is the fact that because people with Angelman can’t speak, it’s hard to know what they want. But Heimer advises people to keep talking to their kids anyway.

“I think they understand much more than they show us. They’re much more aware than we think they are,” she said. “This is why I always tell parents, ‘Talk to your kids all the time, because even though they don’t talk, they probably understand and you manage to increase their receptive vocabulary, like you do for a normal baby. Don’t despair because your child does not talk.”

Heimer added: “I believe that many of the behavioral difficulties we see in Angelman patients evolve from their frustration. They want to express themselves, but they’re unable to do that. The more we give them alternative methods of communication, the happier they will be.”

Ovid therapy offers hope

One medicine that promises to treat not only the symptoms of Angelman but also the underlying pathology of the disease is OV101 (gaboxadol), a pill developed by New York-based Ovid Therapeutics that can either be swallowed whole or dissolved into powder.

Results from the recently completed Phase 2 study (NCT02996305) — also known as the STARS trial — showed that OV101 improved sleep, behavior, and motor abilities in adolescents and adults with Angelman. Ten of the 78 patients involved in STARS were in Israel; the remaining 67 were seen at 15 clinical sites throughout the United States.

Ovid’s positive results with OV101 earlier this year led the company to launch its pivotal Phase 3 NEPTUNE trial involving 60 children ages 4–12 over a 12-week period. On Sept. 12, the company announced that the first patient has been randomized in the trial, with top-line data from the trial to be available in mid-2020.

“There are currently no other therapies in clinical development for Angelman syndrome, and no approved treatments for this disorder exist today,” Amit Rakhit, MD, the company’s chief medical officer, said in a press release. “We hope [this] will result in the first approved medicine for individuals living with this rare neurologic condition.”

Ovid intends to submit a New Drug Application to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for approval of OV101 to treat people with Angelman.

“It’s my hope that OV101 will be covered by the Israeli ‘health basket’ [known in Hebrew as “sal bri’ut”] because it really improved many of the symptoms, and increased quality of life for both the patient and family,” Heimer said, noting that Ovid CEO Jeremy Levin will discuss the drug in detail at the foundation’s next annual conference Dec. 5 at Sheba Medical Center.

“The targeted gene therapies are not going to be a 100% cure,” she said. “The best would be to combine one of the genetic targeting approaches with OV101, which attempts to treat the downstream mechanism of Angelman.”

Heimer said she’s optimistic that OV101, if approved, will be “reasonably priced and available soon” for the patients who need it.

“There’s a lot of hope for Angelman patients these days,” she said. “It’s a very good time to be treating these patients. We didn’t have that hope five years ago.”