Epilepsy Linked to Structural Changes in Brain’s Volume and Thickness, Large Study Shows

Written by |

Patients with epilepsy show a pattern of robust brain structural abnormalities, including alterations in the thickness and volume of the brain’s gray matter.

The findings, stemming from the largest neuroimaging analysis of epilepsy to date, may be helpful for people with Angelman syndrome, because epilepsy affects more than 80 percent of these patients.

The work, led by researchers at University College London (UCL) and the Keck School of Medicine of USC, shows that even patients with common epilepsies, which are usually considered benign when seizures are under control, carry structural brain abnormalities. At this point, the changes detected were mild and researchers haven’t linked them to loss of function.

“We found differences in brain matter even in common epilepsies that are often considered to be comparatively benign. While we haven’t yet assessed the impact of these differences, our findings suggest there’s more to epilepsy than we realize, and now we need to do more research to understand the causes of these differences,” the study’s lead author, Prof. Sanjay Sisodiya, of the UCL Institute of Neurology & Epilepsy Society, said in a press release.

The study, “Structural brain abnormalities in the common epilepsies assessed in a worldwide ENIGMA study,” was published in the journal Brain.

Researchers analyzed brain images collected from 24 research centers across Europe, North and South America, Asia, and Australia as part of the ENIGMA-Epilepsy consortium.

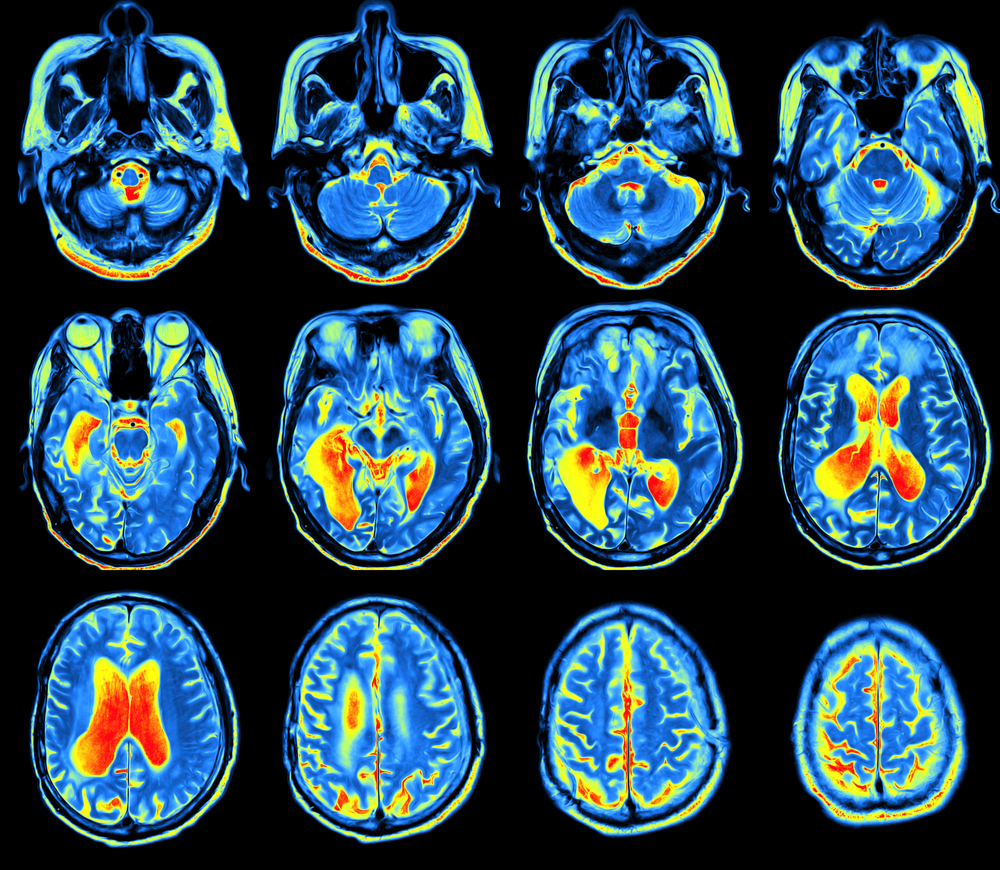

The brain scans – obtained by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) – were collected from 2,149 individuals with epilepsy, and compared to those of 1,727 healthy people. Researchers were aiming to understand which factors influence brain measures in epilepsy.

The epilepsy group images were categorized into four epilepsy subgroups to identify both common features and differences between subgroups.

Compared to the brain scans of the healthy controls, all epilepsy patients showed a decrease in gray matter thickness in the brain’s cortex (the outer layer) and reduced volume in subcortical brain regions. These changes, researchers observed, were linked to a longer duration of epilepsy.

Also, compared to healthy controls, all epilepsy groups showed lower volume in the right thalamus and reduced thickness in the motor cortex. The first integrates sensation and motor signals in the nervous system and was previously linked with epilepsy; the second, the motor cortex, controls the body’s movements.

“The right thalamus also showed evidence of structural compromise across all epilepsy cohorts, re-emphasizing the importance of the thalamus as a major hub in the epilepsy network,” researchers wrote.

These alterations in the brain’s strucuture were detected even in the group of individuals with idiopathic (of unknown origin) generalized epilepsies, characterized by the lack of noticeable brain alterations. Not even an experienced neuroradiologist would detect them when looking at a person’s brain scan.

“Some of the differences we found were so subtle they could only be detected due to the large sample size that provided us with very robust, detailed data,” said the study’s first author, Dr. Christopher Whelan from the Keck School of Medicine of USC and Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland.

When comparing epilepsy subgroups, researchers also detected differences, suggesting the mechanism underlying each epilepsy subtype was different, researchers explained.

“We have identified a common neuroanatomical signature of epilepsy, across multiple epilepsy types. We found that structural changes are present in multiple brain regions, which informs our understanding of epilepsy as a network disorder,” Whelan said.

“Overall, in the largest neuroimaging analysis of epilepsy to date, we demonstrate a pattern of robust brain structural abnormalities within and between syndromes,” the team wrote.

But, “from our study, we cannot tell whether the structural brain differences are caused by seizures, or perhaps an initial insult to the brain, or other consequences of seizures – nor do we know how this might progress over time,” Sisodiya said.

As such, they’re “developing a neuroanatomical map showing which brain measures are key for further studies that could improve our understanding and treatment of the epilepsies,” he said.

“Our consortium plans to investigate more specific neuroanatomical traits and epilepsy phenotypes, explore sophisticated shape and sulcal measures, and eventually conduct genome-wide association analysis of brain measures, to improve our understanding and treatment of the epilepsies,” researchers concluded.