New Telehealth Study May Help Identify Autism Symptoms in Angelman Syndrome Babies

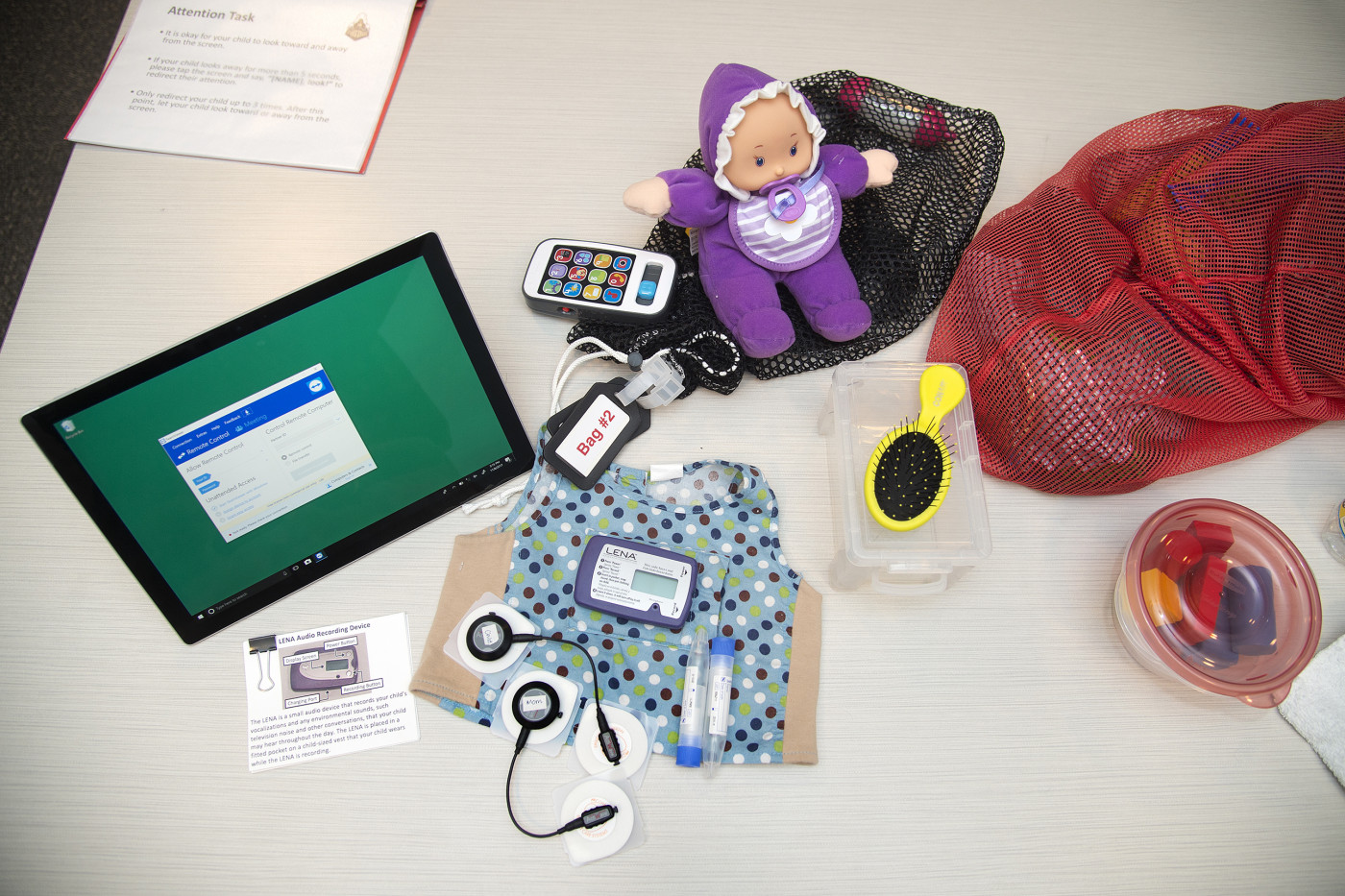

Each kit includes a heart monitor, tablet, toys, items to collect saliva for cortisol measurements, a LENA vocal recorder and a vest to hold the recorder. Credits: Purdue University photo/Mark Simons

Purdue University is conducting a telehealth study to help identify autism symptoms in infants with rare neuro-genetic diseases who might otherwise not be able to receive specialized care.

Results of the study may help children receive tailored therapy earlier than they normally would.

The five-year study will focus on prospective surveillance of autism symptoms in high-risk infants who suffer from neuro-genetic conditions like Angelman syndrome and fragile X syndrome. It has received nearly $1 million in funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

The telehealth method collects vital information and monitors development while the baby is at home, without the need to take the child to a clinic or lab — especially important in babies with rare diseases like Angelman.

Researchers will send families kits containing a heart monitor, a LENA vocal recorder — which measures the early language environment of children from infants up to age 4, a vest to hold the recorder, toys for the baby, and items to collect saliva for cortisol measurements.

Parents will also receive training on activities that are usually done in the lab, including monitoring heart activity and administering eye movement tasks.

“While we have made a lot of progress in autism as far as understanding what the symptoms look like and how to treat and support families, we are still lacking reliable markers of autism before the first year,” Bridgette Tonnsen, the study’s leader and assistant professor of clinical psychology, said in a Purdue University news story by Amy Patterson Neubert.

“The brain changes rapidly during the first year of life, so if we are not detecting children until they are 3 or 4 we are missing a great opportunity to support their development,” said Tonnsen, a member of the Purdue Autism Cluster. “We certainly don’t want to rush a diagnosis, but having some pre-diagnostic interventions could significantly help these children for the long-term.”

Tonnsen said studies of autism emergence in infants often rely on high-risk samples who doctors know will exhibit higher rates of autism later in life. Often researchers will conduct these studies with children who are at high-risk because they have a family member, generally a sibling, who has autism.

Before recruiting families nationwide, the Purdue researchers will work with local families to evaluate the telehealth technology and research procedures in the first part of the study.

“About half of our sample will have autism, and what we learn from their developmental milestones can help us specifically identify what risk factors predict autism,” Tonnsen said.

“We are partnering with the parents to coach them on how to do the research in their homes where the children will be more comfortable rather than traveling long distance to a lab,” she said. “This will be more efficient, cost-effective, more family-friendly and, I think, as a result we will be able to collect more powerful data.”

Tonnsen, who leads the Neurodevelopmental Family Lab, hopes this telehealth study will help other researchers who are working with isolated populations or clinicians diagnosing autism.

Previous telehealth studies have demonstrated that connecting healthcare providers and patients via computer or smartphone for diagnosis and treatment allows for an easier and more cost-effective way to get clinical diagnoses in families who have children with autism spectrum disorders.