Imprinting Mechanism Controls Gene Shutdown in Fetal Development, Researchers Find

Using a process called imprinting, researchers at Howard Hughes Medical Institute have discovered a new mechanism that cells use to control which genes are turned off during fetal development. The finding adds new knowledge to the underling mechanisms of developmental and neurological disorders, such as Angelman syndrome or Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome.

“The new imprinting mechanism may eventually offer a target for treating such developmental failures,” Yi Zhang, PhD, senior author of the study, said in a press release. Zhang is a geneticist at Boston Children’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School.

The article, “Maternal H3K27me3 controls DNA methylation-independent imprinting,” was published in the journal Nature.

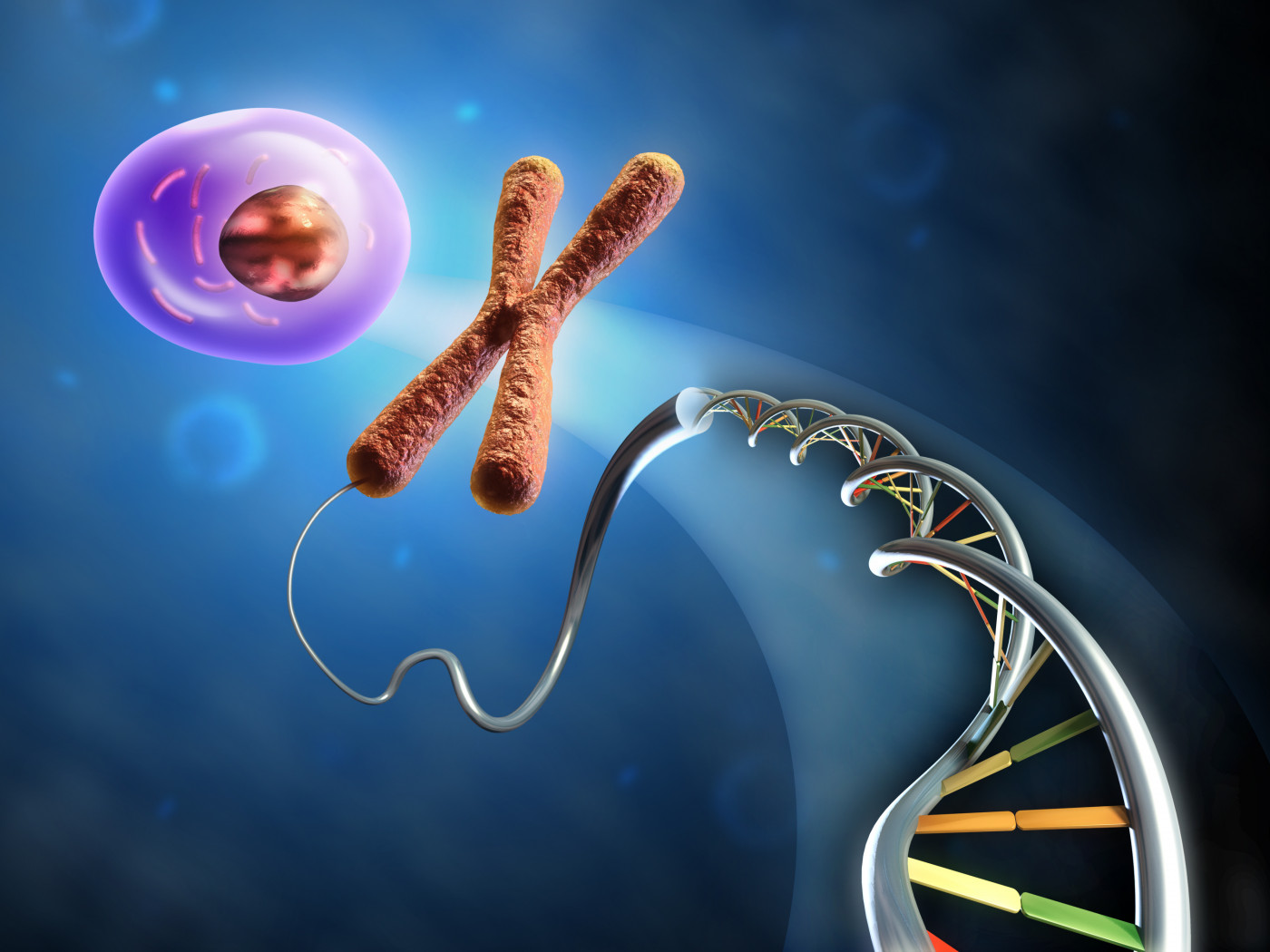

During reproduction, humans inherit two active copies of each gene, one from the mother and one from the father. But for a small number of genes, only one of the copies is working, and the other is turned off permanently.

This mechanism, called imprinting, is tightly regulated, as activation of both copies can result in developmental and neurological disorders.

To date, researchers thought the only mechanism regulating imprinting was the addition of small chemical components, called methyl groups, to the DNA.

But Zhang and colleagues found that cells have an alternative mechanism they use to silence genes. Instead of the methyl groups linked to the DNA sequence, cells can add these chemical elements to proteins called histones, around which the DNA is tightly wrapped.

During the study, the team identified 76 genes in mice that are potential imprinted genes.

While researchers still have much to learn about the imprinting process, Zhang believes that the existence of a second mechanism controlling imprinting shows how important this is during development.

“We believe our study will open up a new field of research,” Zhang said.

In Angelman’s syndrome patients, imprinting on the UBE3A gene is the basis of the disease. In certain regions of the brain, the father-derived copy is silenced, and only the mother’s copy is active. This means that patients with mutations or deletions in the maternal UBE3A have no active copies of the gene in some parts of their brain.

Reversing the imprinting mechanism in this gene may be a means to prevent the development of the disease, but new and extensive research is needed to address this hypothesis.