Geneticist Uses Stem Cells to Study Angelman, Prader-Willi Syndromes

Written by |

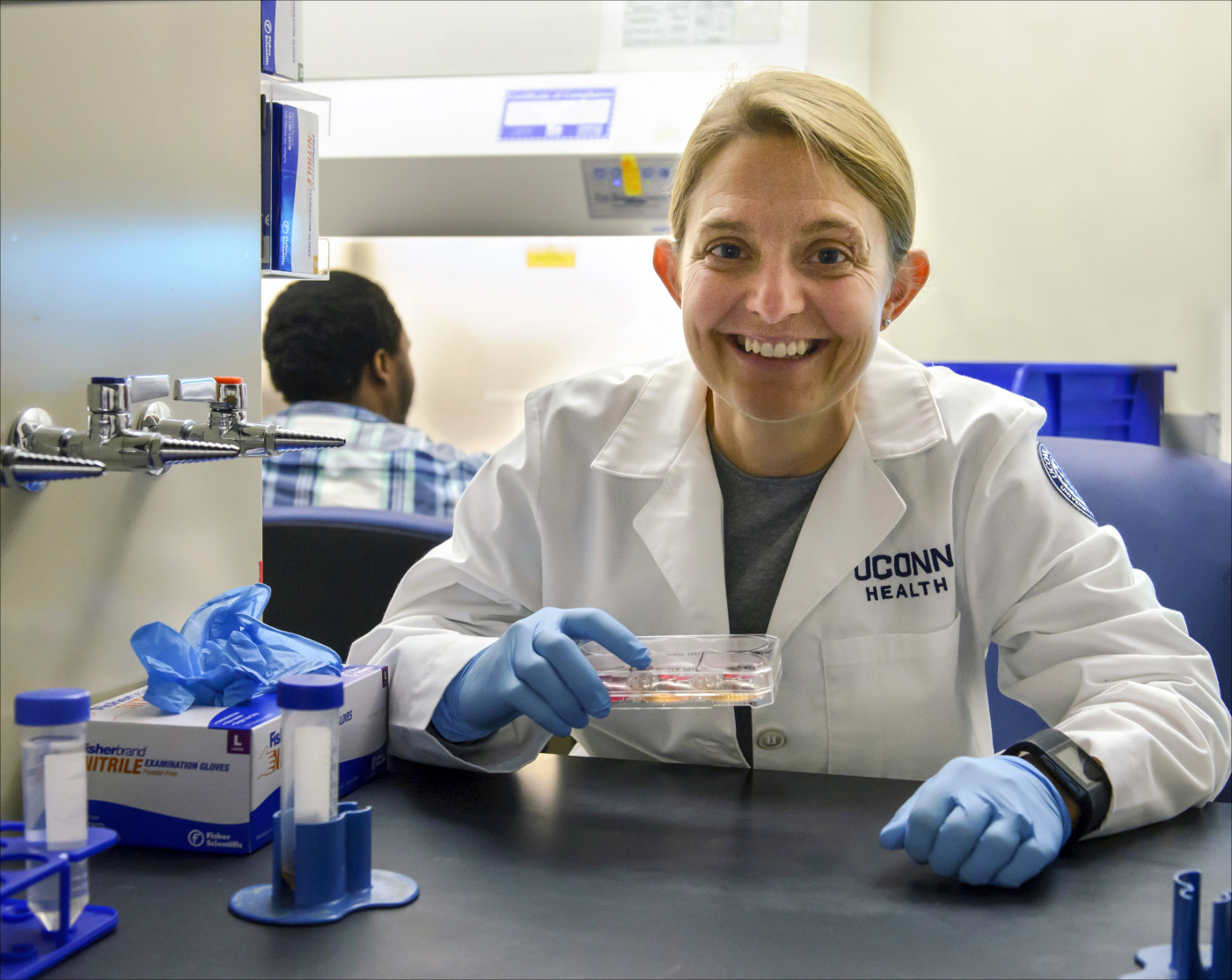

Dr. Stormy Chamberlain. (Photo by Janine Gelineau/UConn Health Multimedia Services)

Two equally rare diseases — Angelman and Prader-Willi syndrome — originate from the same genetic deletion, but lead to radically different outcomes.

These two disorders, along with dup15q syndrome, form the core of research by Stormy Chamberlain, PhD, an associate professor of genetics and genome sciences at the University of Connecticut. Since 2009, Chamberlain has been using induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) at her UConn lab in Farmington to model and study human imprinting disorders.

Crucial to her work is the Connecticut Stem Cell Research Fund, whose creation by lawmakers in 2005 positioned Connecticut as only the third state in the nation to provide public money to support embryonic and human adult stem cell research.

“This really helped establish Connecticut as a real player in stem cell research and allowed us to establish a world-class core facility,” Chamberlain said, estimating that taxpayers have poured at least $100 million into this fund over the last 10 years. “For a small state and a relatively small investment, we did really well.”

Chamberlain was one of two dozen experts who addressed participants at the recent Connecticut Rare Disease Day event, held Feb. 28 at the state legislative office building in Hartford. The gathering attracted some 150 patients, caregivers, members of advocacy groups, lawmakers, and business leaders for a morning of speeches and emotional appeals for more research money.

“The Connecticut Stem Cell Research Fund, the National Institutes of Health (NIH), patient advocacy groups and pharmaceutical companies all partner together to fund rare disease research,” said Chamberlain, who derived the first Prader-Willi iPSCs in 2010, thanks to $200,000 in state funds as well as help from the California-based Foundation for Prader-Willi Research.

Different deletions lead to different diseases

She also focuses on Angelman, getting funding from the Angelman Syndrome Foundation and eventually a $250,000, five-year grant from NIH. Chamberlain now has a small grant from UConn and Alexion, a small pharmaceutical company based in New Haven that’s funding a project in her lab to study a specific therapeutic approach for Angelman.

“The exact same genetic region is responsible for both genetic disorders, and the exact same deletion can cause each disorder,” Chamberlain told Bionews Services — publisher of this website — during a recent interview in Hartford. “If the deletion is on Mom’s chromosome 15, then the child will have Angelman. But if the deletion came from the copy of chromosome 15 from Dad, the child will have Prader-Willi.”

In addition, both diseases occur at roughly the same frequency in the U.S. population. Symptoms of Angelman generally include a small head, a specific facial appearance, speech problems, balance and movement problems, and severe intellectual and developmental disability. Kids with Angelman are generally happy and cheerful in nature and are especially fascinated by water.

In contrast, those with Prader-Willi are constantly hungry; their insatiable appetite often leads to morbid obesity. In addition, they’re often prone to temper tantrums, mood swings, and major depression. They generally have mild to moderate intellectual impairment.

In the 1980s, patients with the disease could expect to live only 20 to 30 years, though things have changed since then; life expectancy for those with either Angelman or Prader-Willi today is considered normal, though neither disorder is curable.

“Over the past few years, obesity has been controlled better among kids with Prader-Willi,” Chamberlain said. “They may die from accidents, but they’re not necessarily dying from their disease as much anymore.”

Using stem cells to study gene regulation

Chamberlain, who also chairs the scientific advisory committee of the Angelman Syndrome Foundation, learned about genomic imprinting as an undergraduate student at Princeton University. Her mentor was genetics professor Shirley Tilghman, PhD, who went on to become president of Princeton. Chamberlain earned her PhD from the University of Florida and has been at UConn for the past nine years.

Induced pluripotent stem cells, equivalent to cells in the first stages of a human embryo, were discovered by Japanese researchers 11 years ago. Because they give rise to an entire embryo, iPSCs have the potential to make any type of cell in the body.

But in Chamberlain’s case, the focus is not on replacement therapies but rather the regulation of genes in people with either Angelman or Prader-Willi syndrome.

“What we do is use iPSCs from patients with these disorders,” she explained. “We use the stem cells to differentiate into neurons, to try to understand how genes are regulated. Angelman iPSCs have only the paternal copy of the chromosome, whereas Prader-Willi iPSCs have only the maternal copy. That allows us to focus on gene regulation of each chromosome separately.”

One fellow scientist has warm words of praise for her years of research.

“Stormy Chamberlain is one of the rarest of scientists working on rare diseases, because she works as hard for the advocacy group as she does in the lab,” said Terry Jo Bichell, PhD, director and scientific officer at the Angelman Biomarkers and Outcome Measures Alliance. “She is a top-notch scientist, and her work will contribute to life-changing treatments for many diseases.”