Early Enriching Intervention Helps Restore Behaviors in Mouse Study

Early intervention with environmental stimulation appears to have restored motor coordination and behaviors in a mouse model of Angelman syndrome.

The protocol was more successful in male mice than in females, suggesting that “slightly different therapeutic approaches may need to be taken with males and females undergoing treatment for [Angelman syndrome],” the researchers wrote.

The analysis was published in the journal Brain and Behavior, in the study “Sex-dependent influence of postweaning environmental enrichment in Angelman syndrome model mice.”

Angelman syndrome is a developmental disorder caused by a faulty UBE3A gene. The condition is marked by developmental delays, intellectual disability, seizures, impaired speech, and other behavioral abnormalities, including motor deficits, hyperactivity, and anxiety.

With no cure yet for Angelman, available treatments focus on controlling seizures and managing physical and behavioral symptoms.

Emerging evidence suggests that early-life experiences may affect the course of developmental disorders, and early intervention may be an effective treatment.

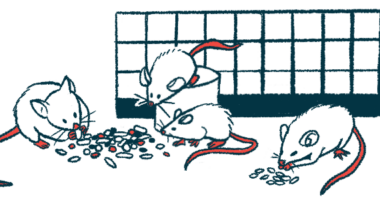

A strategy called environmental enrichment — an experimental method that provides additional sensory, cognitive, physical, and social stimulation — has been able to correct behavioral deficits in mouse models of various psychiatric disorders.

In this report, scientists at Augustana University in South Dakota applied environmental enrichment to young male and female mice missing the UBE3A gene and healthy controls.

Three weeks after birth, the pups were weaned, separated by sex, and randomly assigned to environmentally enriched housing — a clear plastic cage with a variety of shelter options, where mice could run and climb, explore different textures, and dig and burrow — or a conventional mouse cage as a comparison.

After six weeks, both male and female Angelman mice in the conventional housing gained significant weight, a documented characteristic of this mouse model. Following exposure to environmental enrichment, Angelman mice weighed significantly less than the other mice and were indistinguishable from healthy control mice.

In male Angelman mice, the expected deficit in marble-burying was unaffected by environmental enrichment after six weeks. Two weeks later, a follow-up test showed that environmental enrichment rescued marble-burying deficits entirely.

Conversely, female Angelman mice did significantly improve with six weeks of environmental enrichment compared to those in standard housing, but in the two-week follow-up test, the previous improvements had disappeared.

Next, mice underwent an open field behavior test — to determine general activity levels, overall motor activity, and the exploration habits of rodent models. As expected, the distance traveled in the open field by Angelman mice housed in standard cages was significantly less than healthy mice from the same housing.

After seven weeks of environmental enrichment, the distance traveled by male Angelman mice, but not female mice, significantly improved compared to those in conventional cages and were no different than healthy mice in standard housing.

In all Angelman mice, environmental enrichment had no impact on the number of rearing movements, a typical exploratory behavior, and entries into the exposed center zone of the open field compared to normal mice.

Environmental enrichment improved the performance of male Angelman mice, but not female mice, on the rotarod test, which measures motor abilities by riding time and endurance on a rotating rod. Enrichment also improved the rotarod performance of healthy mice. A second test two days later confirmed these findings.

Finally, mice were subjected to the forced swim test, which assessed active (swimming and climbing) or passive (immobility) behavior when forced to swim in a cylinder. Similar to the open field and rotarod tests, environmental enrichment significantly affected the performance of the Angelman mice but in the males only.

“These findings are consistent with a body of evidence showing that [environmental enrichment] is effective at correcting some phenotypes [features] in mouse models of neurodevelopmental disorders,” the researchers wrote. “We recapitulated the behavioral deficits in both male and female [Angelman syndrome] mice but found that our [environmental enrichment] protocol was far more successful at normalizing these phenotypes in male mice than in female mice.”