Angelman Expert Terry Jo Bichell Earns PhD to Help Find Cure for Son’s Disease

Written by |

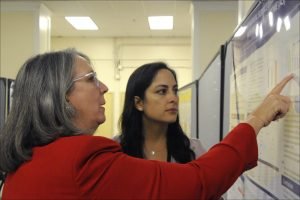

A-BOM's Terry Jo Bichell (Photos by Larry Luxner)

WASHINGTON — Terry Jo Bichell earned a master’s degree in public health, became an expert in pregnancy-related deaths, and made documentary films about women’s health projects in Côte d’Ivoire, Gambia, Nigeria and Senegal.

But nothing prepared her for the news that her baby, Louie, had Angelman syndrome. It was 17 years ago, and back then, little was known about the disease.

“Every woman in the world has a one-in-10,000 chance of having a child with Angelman, and every woman in the world is born with 10,000 eggs, so it’s just a roulette wheel,” she said. “We don’t know why” some children develop it and others don’t, she said.

But not every woman whose child has Angelman goes back to college with one goal in mind: finding a cure for the rare genetic disorder.

Bichell, 58, did just that. In 2009, she enrolled in the neuroscience graduate program at Vanderbilt University’s Brain Institute, eventually earning a PhD. Today, she’s director and scientific officer of the Angelman Biomarkers and Outcome Measures (ABOM) Alliance.

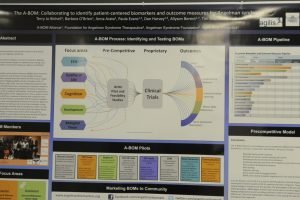

ABOM is a collaboration of two patient advocacy groups, doctors, scientists and pharmaceutical companies. The advocacy groups are the Angelman Syndrome Foundation and FAST, which stands for the Foundation for Angelman Syndrome Therapeutics.

Bichell also serves as Tennessee’s volunteer ambassador for the Rare Action Network, a project of the National Organization for Rare Disorders, or NORD.

Mom knew something was wrong

“Angelman has the same prevalence as Huntington’s, but the reason you haven’t heard of Angelman is that people with Huntington’s can talk,” she told Angelman Syndrome News on the sidelines of the recent NORD Rare Disease Summit in Washington. “They can tell how you how they feel, whereas people with Angelman can’t, so their families have to speak for them.”

Scientists didn’t isolate the gene that causes Angelman until 1995, and a proper diagnosis wasn’t available until the late 1990s. These days, Bichell said, “almost every school district has one or two kids with this disorder. Almost every primary care doctor will see one person with Angelman in the life of their practice.”

Bichell and her husband, Dr. David Bichell, chief of pediatric cardiac surgery at Vanderbilt’s Monroe Carell Jr. Children’s Hospital, had Louie in 1999.

“I was a nurse midwife at the time, with a degree in public health, and I had taught hundreds of ladies how to breastfeed their children. I knew a lot about being a mom,” said Bichell, who also has degrees from Boston University and Baltimore’s Johns Hopkins University. “So when Louie was born, I just knew something wasn’t right.”

Even though her son was extraordinarily cheerful, Bichell — who also has four daughters — said she had a “weird feeling” that he wasn’t really communicating with her.

“When it was the normal time to sit up, he didn’t sit up,” she said. “Finally, by the age of 1, we took him to the pediatrician, who agreed there was something wrong. She sent him to a neurologist, who diagnosed him with cerebral palsy. But I felt pretty sure — and so did my husband — that that couldn’t be correct.”

A desperate quest for knowledge

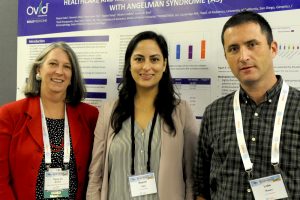

Determined to find answers, Bichell brought her son, then 14 months old, to geneticist Ken Lyons Jones at the University of California, San Diego.

“He took a tuning fork and put it on my son’s knee. And suddenly, my son just cracked up laughing and laughing.”

When the official diagnosis arrived, Bichell was teaching at a midwifery school in San Miguel de Allende, Mexico.

“I was in the middle of nowhere, so I walked three miles to the nearest Internet café and started looking up Angelman syndrome,” she recalled. “I learned that the very first international conference in the world on this disease was going to take place in Finland a month later.”

Bichell made it her business to attend the conference — along with 500 others — in the Finnish city of Tampere. There she ran into Dr. Art Beaudet, the scientist who discovered the Angelman gene. Armed with the knowledge she gained there, Bichell tried to convince researchers to pursue a treatment idea she had developed. When they wouldn’t, she decided to pursue it herself, as part of a Vanderbilt team. The treatment involved turning on a silenced gene.

In Angelman syndrome, genes from either the mother or father are silenced. When the paternal copy of the UBE3A gne on chromosome 15 is turned off, the maternal copy cannot produce the proteins needed for normal nervous system functioning. The result is Angelman syndrome.

“At that point, I had this idea in mind to make stem cells out of the skin of Angelman patients, turn those into neurons in a dish, and expose them to compounds and medications to see if any of them would activate the paternal gene,” she said. “I thought, if we could just turn on the paternal gene, we should be able to fix it. I was on a roll.”

Angelman more widespread than first thought

However, the principal investigator working on the project suddenly resigned.

“That was a huge setback. The only way for me to do my project would be for another lab to take on me and my project,” she said. “I went all around Vanderbilt trying to find a different PI [principal investigator]. I ended up doing my PhD on Huntington’s disease.”

Asked if Angelman has anything to do with geography or ethnic origin, Bichell said she doesn’t think so.

“As recently as five years ago, it was thought there were no cases in China, but that turned out to be just a lack of diagnoses. Chinese researchers are already publishing on the disorder,” she said. “When my son was diagnosed in 2000, we were living in San Diego and were told there were no cases in Mexico. Yet in San Diego we had many cases in people of Mexican ancestry. Now, 17 years later, we’ve got lots of cases in Mexico.”

At the moment, at least five organizations are developing revolutionary treatments that “if they work for Angelman syndrome, will work for lots of other disorders,” Bichell said. The five are Agilis Biotherapeutics, Ionis Pharmaceuticals, Ovid Therapeutics, Roche and Penn Medicine.

Bichell said that as she was writing her doctoral dissertation, Jodi A. Cook, the chief operating officer of Agilis, asked her to consider leading the ABOM alliance. The alliance now has three projects that have been funded — two by foundations and one by a corporation — and three in the pipeline.

Bichell a ‘true idol,’ says FAST’s Allyson Berent

While Bichell thinks a cure for Angelman syndrome is around the corner, she worries it might not arrive soon enough to help her son, who is now a young adult.

“Louie can’t bathe himself, he can’t shave himself, he can’t brush his own teeth. But we have babysitters who help out a lot,” she said, estimating that it costs at least $30,000 a year to treat and care for Louie. That estimate doesn’t include medicine, although she said his medical expenses have been relatively low.

“Most kids with Angelman have terrible seizures,” she said. “Our kid hasn’t had a seizure in 14 years, so we’re really lucky that way. He takes seizure meds and has been really healthy.”

Allyson Berent, chief scientific officer at FAST, called Bichell “a true idol for me and my family.”

“She was one of the first parents we talked to after our daughter Quincy was diagnosed at 7 months old,” Berent said in an email. “She and her husband Dave made it clear that they live a wonderful life, even with having a child with Angelman, but they know life could be so much better for Louie if we could bring meaningful therapeutics forward.”

Berent said she admires Bichell so much that she and her husband named their third daughter “Piper Jo.” They did so because, as Berent said, Terry Jo “is a fighter, a fierce advocate and a scholar — all things we wish for our children.”